Hello reddit!

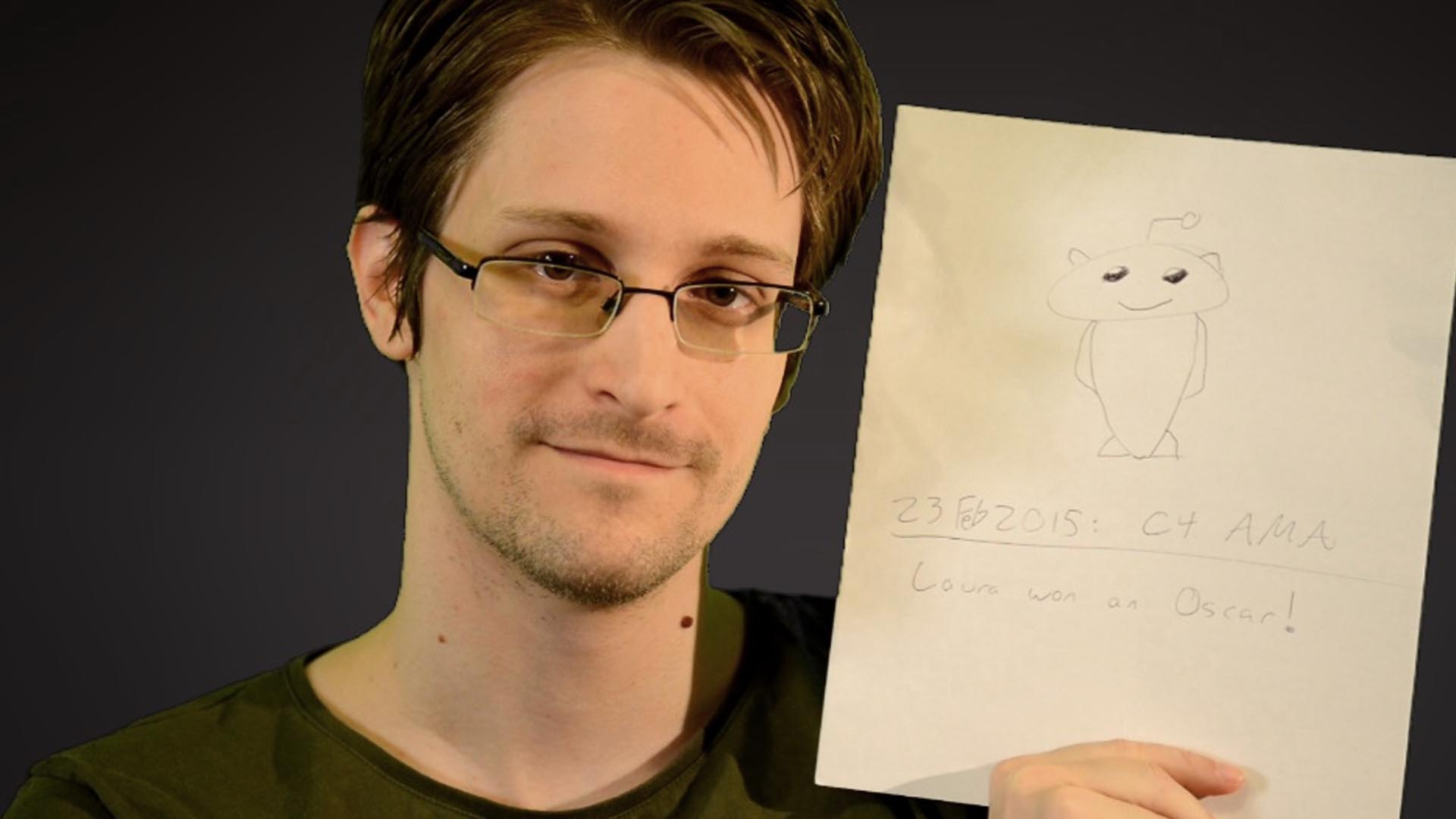

Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald here together in Los Angeles, joined by Edward Snowden from Moscow.

A little bit of context: Laura is a filmmaker and journalist and the director of CITIZENFOUR, which last night won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

The film debuts on HBO tonight at 9PM ET| PT (http://www.hbo.com/documentaries/citizenfour).

Glenn is a journalist who co-founded The Intercept (https://firstlook.org/theintercept/) with Laura and fellow journalist Jeremy Scahill.

Laura, Glenn, and Ed are also all on the board of directors at Freedom of the Press Foundation. (https://freedom.press/)

We will do our best to answer as many of your questions as possible, but appreciate your understanding as we may not get to everyone.

Proof: http://imgur.com/UF9AO8F

UPDATE: I will be also answering from /u/SuddenlySnowden.

https://twitter.com/ggreenwald/status/569936015609110528

UPDATE: I’m out of time, everybody. Thank you so much for the interest, the support, and most of all, the great questions. I really enjoyed the opportunity to engage with reddit again — it really has been too long.

Russian journalist Andrei Soldatov has described your daily life as circumscribed by Russian state security services, which he said control the circumstances of your life there. Is this accurate? What are your interactions with Russian state security like? With Russian government representatives generally?

[Snowden] Good question, thanks for asking.

The answer is “of course not.” You’ll notice in all of these articles, the assertions ultimately come down to speculation and suspicion. None of them claim to have any actual proof, they’re just so damned sure I’m a russian spy that it must be true.

And I get that. I really do. I mean come on – I used to teach “cyber counterintelligence” (their term) at DIA.

But when you look at in aggregate, what sense does that make? If I were a russian spy, why go to Hong Kong? It’s would have been an unacceptable risk. And further – why give any information to journalists at all, for that matter, much less so much and of such importance? Any intelligence value it would have to the russians would be immediately compromised.

If I were a spy for the russians, why the hell was I trapped in any airport for a month? I would have gotten a parade and a medal instead.

The reality is I spent so long in that damn airport because I wouldn’t play ball and nobody knew what to do with me. I refused to cooperate with Russian intelligence in any way (see my testimony to EU Parliament on this one if you’re interested), and that hasn’t changed.

At this point, I think the reason I get away with it is because of my public profile. What can they really do to me? If I show up with broken fingers, everybody will know what happened.

Don’t you fear that at some point you will be used as leverage in a negotiation? eg; “if you drop the sanctions we give you Snowden”

[Snowden] It is very realistic that in the realpolitik of great powers, this kind of thing could happen. I don’t like to think that it would happen, but it certainly could.

At the same time, I’m so incredibly blessed to have had an opportunity to give so much back to the people and internet that I love. I acted in accordance with my conscience and in so doing have enjoyed far more luck than any one person can ask for. If that luck should run out sooner rather than later, on balance I will still – and always – be satisfied.

Laura, are you still detained for extra screening when you fly in the US?

[Poitras] The detentions have thankfully stopped, at least for now. Starting in 2006, after I came back from making a film about Iraq’s first election, I was stopped and detained at the US border over 40 times, often times for hours. After I went public with my experiences (Glenn broke the story in 2012), the harassment stopped. Unfortunately there are countless others who aren’t so lucky.

Can you explain what your life in Moscow is like?

[Snowden] Moscow is the biggest city in Europe. A lot of people forget that. Shy of Tokyo, it’s the biggest city I’ve ever lived in. I’d rather be home, but it’s a lot like any other major city.

I saw that you used GPG to encrypt the document archives and the movie stated that Laura and Glenn are using Tails to analyse documents. How do you collaborate? E.g. share a document, tag it together, share notes etc? Using tools like the overview project (AP, Knight Foundation) seems impossible when wanting to protect documents properly.

[Poitras] It would have been impossible for us to work on the NSA stories and make Citizenfour without many encryption tools that allowed us to communicate more securely. In fact, in the credits we thank several free software projects for making it all possible. I can’t really get into our specific security process, but on the The Intercept’s security experts, Micah Lee, wrote a great post about helping Glenn and I when we first got in contact with Snowden:https://firstlook.org/theintercept/2014/10/28/smuggling-snowden-secrets/

It’s definitely important that we support these tools so the creators can make them easier to use. They are incredibly underfunded for how important they are. You can donate to Tails, Tor and a few other projects here:https://freedom.press/bundle/encryption-tools-journalists

To Greenwald & Poitras: What was the most alarming revelation(s) you discovered throughout this process, and is there more to come?

[Greenwald] For me personally, the most shocking revelation was the overall one that the explicit goal of the NSA and its allies is captured by the slogan “collect it all” – meaning they want to convert the internet into a place of limitless, mass surveillance, which is another way of saying they literally want to eliminate privacy in the digital age:

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/jul/15/crux-nsa-collect-it-all

There is definitely more significant reporting to come. Our colleagues at the Intercept – Jeremy Scahill and Josh Begley – just last week reported one of the most significant stories yet on the NSA and GCHQ’s ‘s hacking practices:

https://firstlook.org/theintercept/2015/02/19/great-sim-heist/

To Snowden: What validation do we have that Putin is being honest about NOT spying in Russia?

[Snowden] To tag on to the Putin question: There’s not, and that’s part of the problem world-wide. We can’t just reform the laws in one country, wipe our hands, and call it a day. We have to ensure that our rights aren’t just being protected by letters on a sheet of paper somewhere, or those protections will evaporate the minute our communications get routed across a border. The only way to ensure the human rights of citizens around the world are being respected in the digital realm is to enforce them through systems and standards rather than policies and procedures.

Why did you wait so long to release such an important finding?

[Greenwald] We’ve been reporting continuously on huge stories without pause for 18 months, using editors, reporters, and experts from all over the world.

These documents are complex and take time to process, understand, and research.

If we rush the reporting and make mistakes, we’ll be doing a huge favor to proponents of mass surveillance, and then people like you will be coming and asking – reasonably: “why did you rush all this? Why didn’t you make sure the reporting was accurate before publishing it”?

Snowden expressly asked us to vet the documents carefully and subject them to the reporting process so that the public could be informed in a clear and accurate way. With an archive this vast and complicated, that takes time.

I hardly think anyone can complain that there hasn’t been enough reporting done – it’s been an unprecedentedly continuous and rapid stream of stories. The public needs time to understand and digest them, and good reporting takes time to do.

How can we make sure that people still want to leak important information when everyone who does so puts the rest of their lives at stake?

[Snowden] Whistleblower protection laws, a strong defense of the right for someone charged with political crimes to make any defense they want (currently in the US, someone charged with revealing classified information is entirely prohibited from arguing before the jury that the programs were unlawful, immoral, or otherwise wrongful), and support for the development of technically and legally protected means of communications between sources and journalists.

The sad truth is that societies that demand whistleblowers be martyrs often find themselves without either, and always when it matters the most.

How do you feel about the “nothing to hide” argument?

[Greenwald] I did a TED talk specifically to refute that inane argument, here:

http://www.ted.com/talks/glenn_greenwald_why_privacy_matters?language=en

Mr. Snowden, if you had a chance to do things over again, would you do anything differently? If so, what?

[Snowden] I would have come forward sooner. I talked to Daniel Ellsberg about this at length, who has explained why more eloquently than I can.

Had I come forward a little sooner, these programs would have been a little less entrenched, and those abusing them would have felt a little less familiar with and accustomed to the exercise of those powers. This is something we see in almost every sector of government, not just in the national security space, but it’s very important:

Once you grant the government some new power or authority, it becomes exponentially more difficult to roll it back. Regardless of how little value a program or power has been shown to have (such as the Section 215 dragnet interception of call records in the United States, which the government’s own investigation found never stopped a single imminent terrorist attack despite a decade of operation), once it’s a sunk cost, once dollars and reputations have been invested in it, it’s hard to peel that back.

Don’t let it happen in your country.

Laura, in your recent interview with David Carr, you expressed your commitment as an artist to convey the emotions you feel as a target of state surveillance. Do you also consider yourself a journalist? If so, do you think there is a tension between artistic expression and journalistic integrity?

[Poitras] Thanks for the kind words. I definitely consider myself a journalist, as well as an artist and a filmmaker. In my mind, it’s not a question about whether I am one or the other. Documentary films needs to do more than journalism – they need to communicate something that is more universal.

What’s the best way to make NSA spying an issue in the 2016 Presidential Election? It seems like while it was a big deal in 2013, ISIS and other events have put it on the back burner for now in the media and general public. What are your ideas for how to bring it back to the forefront?

[Greenwald] The key tactic DC uses to make uncomfortable issues disappear is bipartisan consensus. When the leadership of both parties join together – as they so often do, despite the myths to the contrary – those issues disappear from mainstream public debate.

The most interesting political fact about the NSA controversy, to me, was how the divisions didn’t break down at all on partisan lines. Huge amount of the support for our reporting came from the left, but a huge amount came from the right. When the first bill to ban the NSA domestic metadata program was introduced, it was tellingly sponsored by one of the most conservative Tea Party members (Justin Amash) and one of the most liberal (John Conyers).

The problem is that the leadership of both parties, as usual, are in full agreement: they love NSA mass surveillance. So that has blocked it from receiving more debate. That NSA program was ultimately saved by the unholy trinity of Obama, Nancy Pelosi and John Bohener, who worked together to defeat the Amash/Conyers bill.

The division over this issue (like so many other big ones, such as crony capitalism that owns the country) is much more “insider v. outsider” than “Dem v. GOP”. But until there are leaders of one of the two parties willing to dissent on this issue, it will be hard to make it a big political issue.

That’s why the Dem efforts to hand Hillary Clinton the nomination without contest are so depressing. She’s the ultimate guardian of bipartisan status quo corruption, and no debate will happen if she’s the nominee against some standard Romney/Bush-type GOP candidate. Some genuine dissenting force is crucial.

[Snowden] This is a good question, and there are some good traditional answers here. Organizing is important. Activism is important.

At the same time, we should remember that governments don’t often reform themselves. One of the arguments in a book I read recently (Bruce Schneier, “Data and Goliath”), is that perfect enforcement of the law sounds like a good thing, but that may not always be the case. The end of crime sounds pretty compelling, right, so how can that be?

Well, when we look back on history, the progress of Western civilization and human rights is actually founded on the violation of law. America was of course born out of a violent revolution that was an outrageous treason against the crown and established order of the day. History shows that the righting of historical wrongs is often born from acts of unrepentant criminality. Slavery. The protection of persecuted Jews.

But even on less extremist topics, we can find similar examples. How about the prohibition of alcohol? Gay marriage? Marijuana?

Where would we be today if the government, enjoying powers of perfect surveillance and enforcement, had — entirely within the law — rounded up, imprisoned, and shamed all of these lawbreakers?

Ultimately, if people lose their willingness to recognize that there are times in our history when legality becomes distinct from morality, we aren’t just ceding control of our rights to government, but our agency in determing thour futures.

How does this relate to politics? Well, I suspect that governments today are more concerned with the loss of their ability to control and regulate the behavior of their citizens than they are with their citizens’ discontent.

How do we make that work for us? We can devise means, through the application and sophistication of science, to remind governments that if they will not be responsible stewards of our rights, we the people will implement systems that provide for a means of not just enforcing our rights, but removing from governments the ability to interfere with those rights.

You can see the beginnings of this dynamic today in the statements of government officials complaining about the adoption of encryption by major technology providers. The idea here isn’t to fling ourselves into anarchy and do away with government, but to remind the government that there must always be a balance of power between the governing and the governed, and that as the progress of science increasingly empowers communities and individuals, there will be more and more areas of our lives where — if government insists on behaving poorly and with a callous disregard for the citizen — we can find ways to reduce or remove their powers on a new — and permanent — basis.

Our rights are not granted by governments. They are inherent to our nature. But it’s entirely the opposite for governments: their privileges are precisely equal to only those which we suffer them to enjoy.

We haven’t had to think about that much in the last few decades because quality of life has been increasing across almost all measures in a significant way, and that has led to a comfortable complacency. But here and there throughout history, we’ll occasionally come across these periods where governments think more about what they “can” do rather than what they “should” do, and what is lawful will become increasingly distinct from what is moral.

In such times, we’d do well to remember that at the end of the day, the law doesn’t defend us; we defend the law. And when it becomes contrary to our morals, we have both the right and the responsibility to rebalance it toward just ends.

Laura: Will you release more footage of the meetings held with Snowden in Hong Kong?

[Poitras] Yes, I do plan to release more footage from Hong Kong shoot. On the first day we met Ed, Glenn conducted a long interview (4-5 hours) that is extraordinary. I also conducted a separate interview with Ed re: technical questions. The time constraints of a feature film made it impossible to include everything. I will release more.

I also filmed incredible footage with Julian Assange/WikiLeaks that we realized in the edit room was a separate film.

How did you guys feel about about Neil Patrick Harris’ “for some treason” joke last night?

[Snowden] Wow the questions really blew up on this one. Let me start digging in…

To be honest, I laughed at NPH. I don’t think it was meant as a political statement, but even if it was, that’s not so bad. My perspective is if you’re not willing to be called a few names to help out your country, you don’t care enough.

“If this be treason, then let us make the most of it.”

[Greenwald] Here’s a little insight into how digital age media works:

I learned of NPH’s joke after I left the stage (he said it as we were walking off). I was going to tweet something about it and decided it was too petty and inconsequential even to tweet about – just some lame word-play Oscar joke from a guy who had just been running around onstage in his underwear moments before. So I forgot about it. My reaction was similar to Ed’s, though I did think the joke was lame.

A couple hours later at a post-Oscar event, a BuzzFeed reporter saw me and asked me a bunch of questions about the film and the NSA reporting, one of which was about that “treason” joke. I laughed, said it was just a petty pun and I didn’t want to make a big deal out of it, but then said I thought it was stupid and irresponsible to stand in front of a billion people and accuse someone of “treason” who hasn’t even been charged with it, let alone convicted of it.

Knowing that would be the click-worthy comment, BuzzFeed highlighted that in a headline, making it seem like I had been on the warpath, enraged about this, convening a press conference to denounce this outrage. In fact, I was laughing about it the whole time when I said it, as the reporter noted. But all that gets washed away, and now I’m going to hear comments all day about how I’m a humorless scold who can’t take a good joke, who gets furious about everything, etc. etc.

Nobody did anything wrong here, including BuzzFeed. But it’s just a small anecdote illustrating how the imperatives of internet age media and need-for-click headlines can distort pretty much everything they touch.

Edward, a friend of mine works for the NSA. He still actively denies that anything you have done or said is legitimate, completely looking past any documented proof that you uncovered and released. Is this because at lower levels of the agency, they don’t see what’s going on in the intelligence gathering section? Or do you suspect he simply refuses to see any wrongdoing by his employer?

[Snowden] So when you work at NSA, you get sent what are called “Agency-All” emails. They’re what they sound like: messages that go to everybody in the workforce.

In addition to normal bureaucratic communications, they’re used frequently for opinion-shaping internally, and are often classified at least in part. They assert (frequently without evidence) what is true or false about cases and controversies in the public news that might influence the thinking about the Intelligence Community workforce, while at the same time reminding them how totally screwed they’ll be if they talk to a journalist (while helpfully reminding them to refer people to the public affairs office).

Think about what it does to a person to come into their special top-secret office every day and get a special secret email from “The Director of NSA” (actually drafted by totally different people, of course, because senior officials don’t have time to write PR emails) explaining to you why everything you heard in the news is wrong, and how only the brave, patriotic, and hard-working team of cleared professionals in the IC know the truth.

Think about how badly you want to believe that. Everybody wants to be valued and special, and nobody wants to think they’ve perhaps contributed to a huge mistake. It’s not evil, it’s human.

Tell your friend I was just like they are. But there’s a reason the government has — now almost two years out — never shown me to have told a lie. I don’t ask anybody to believe me. I don’t want anybody to believe me. I want you to look around and decide for yourself what you believe, independent of what people says, indepedent of what’s on TV, and independent of what your classified emails might claim.

Glenn, if you had a chance with no consequences to say anything at the podium last night, what would it had been?

[Greenwald] I probably would have said what I said the day before when CITIZENFOUR won the Independent Spirit Award and Laura, Dirk and Mathilde generously asked me to say something:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=udfKDCI3i2s

Or maybe I would have just read from some documents that I can’t wait to be reported and disclosed, along with some nice visuals of those docs.

Mr. Snowden, what do you think about the latest news kaspersky broke? I understand they don’t talk about victims and aggressors because it’s their business model. But do you think they should name the nsa as an aggressor when they know about?

[Snowden] The Kaspersky report on the “Equation Group” (they appear to have stopped short of naming them specifically as NSA, although authorship is clear) was significant, but I think more significant is the recent report on the joint UK-UK hacking of Gemalto, a Dutch company that produces critical infrastructure used around the world, including here at home.

Why? Well, although firmware exploitation is nasty, it’s at least theoretically reparable: tools could plausibly be created to detect the bad firmware hashes and re-flash good ones. This isn’t the same for SIMs, which are flashed at the factory and never touched again. When the NSA and GCHQ compromised the security of potentially billions of phones (3g/4g encryption relies on the shared secret resident on the sim), they not only screwed the manufacturer, they screwed all of us, because the only way to address the security compromise is to recall and replace every SIM sold by Gemalto.

Our governments – particular the security branches – should never be weighing the equities in an intelligence gathering operation such that a temporary benefit to surveillance regarding a few key targets is seen as more desireable than protecting the communications of a global system (and this goes double when we are more reliant on communications and technology for our economy productivity than our adversaries).

So far Gemalto is claiming SIMs are still secure. http://www.cnet.com/news/sim-card-maker-gemalto-says-its-cards-are-secure-despite-hack/ Not believing them at this point. Theoretically I would believe them if they had found some traces of an intrusion and had figured out that it would not have allowed access to private keys. But based on just their claims of security, not buying it yet.

[Snowden] I wouldn’t believe them either. When we’re talking about how to weight reliability between specific government documents detailing specific Gemalto employees and systems (and tittering about how badly they’ve been owned) against a pretty breezy and insubstantial press release from a corporation whose stock lost 500,000,000 EUR in value in a single day, post-report, I know which side I come down on.

That’s not to say Gemalto’s claims are totally worthless, but they have to recognize that their business relies on trust, and if they try to wave away a serious compromise, it’ll cost them more than it saves them.

We’ve now known about the scary stuff happening at the NSA for quite some time. And yet from what I’ve seen, there’s been no real effort to stop it. What are your thoughts on what we, as regular citizens, can do now?

[Snowden] One of the biggest problems in governance today is the difficulty faced by citizens looking to hold officials to account when they cross the line. We can develop new tools and traditions to protect our rights, and we can do our best to elect new and better representatives, but if we cannot enforce consequences on powerful officials for abusive behavior, we end up in a system where the incentives reward bad behavior post-election.

That’s how we end up with candidates who say one thing but, once in power, do something radically different. How do you fix that? Good question.

Mr Snowden, do you feel that your worst fear is being realized, that most people don’t care about their privacy?

[Snowden] To answer the question, I don’t. Poll after poll is confirming that, contrary to what we tend to think, people not only care, they care a lot. The problem is we feel disempowered. We feel like we can’t do anything about it, so we may as well not try.

It’s going to be a long process, but that’s starting to change. The technical community (and a special shoutout to every underpaid and overworked student out there working on this — you are the noble Atlas lifting up the globe in our wildly inequitable current system) is in a lot of way left holding the bag on this one by virtue of the nature of the problems, but that’s not all bad. 2013, for a lot of engineers and researchers, was a kind of atomic moment for computer science. Much like physics post-Manhattan project, an entire field of research that was broadly apolitical realized that work intended to improve the human condition could also be subverted to degrade it.

Politicians and the powerful have indeed got a hell of a head start on us, but equality of awareness is a powerful equalizer. In almost every jurisdiction you see officials scrambling to grab for new surveillance powers now not because they think they’re necessary — even government reports say mass surveillance doesn’t work — but because they think it’s their last chance.

Maybe I’m an idealist, but I think they’re right. In twenty years’ time, the paradigm of digital communications will have changed entirely, and so too with the norms of mass surveillance.

Don’t you find it kind of depressing how little the world was actually moved by the revelations? I do. For a few days at a time it was the biggest news story ever but barely anything has changed and people are still using Google, Apple et al. in the same ways. The news in general is just so transient, watching the documentary just brought it all back. It felt like it might actually amount to something but as far as I can tell, even with the courts recently ruling that GCHQs actions were illegal for many years and NSAs whole program amounting to nothing, no significant legislation has passed and for all we know they are still rapidly expanding their programs.

[Greenwald] I think much has changed. The US Government hasn’t restricted its own power, but it’s unrealistic to expect them to do so.

There are now court cases possible challenging the legality of this surveillance – one federal court in the US and a British court just recently found this spying illegal.

Social media companies like Facebook and Apple are being forced by their users to install encryption and other technological means to prevent surveillance, which is a significant barrier.

Nations around the world (such as Brazil and Germany) are working together in unison to prevent US hegemony over the internet and to protect the privacy of their own citizens.

And, most of all, because people now realize the extent to which their privacy is being compromised, they can – and increasingly are – using encryption and anonymizers to protect their own privacy and physically prevent mass surveillance (see here: http://www.wired.com/2014/05/sandvine-report/).

All of these changes are very significant. And that’s to say nothing of the change in consciousness around the world about how hundreds of millions of people think about these issues. The story has been, and continues to be, huge in many countries outside the US.

[Snowden] To dogpile on to this, many of the changes that are happening are invisible because they’re happening at the engineering level. Google encrypted the backhaul communications between their data centers to prevent passive monitoring. Apple was the first forward with an FDE-by-default smartphone (kudos!). Grad students around the world are trying to come up with ways to solve the metadata problem (the opportunity to monitor everyone’s associations — who you talk to, who you sleep with, who you vote for — even in encrypted communications).

The biggest change has been in awareness. Before 2013, if you said the NSA was making records of everybody’s phonecalls and the GCHQ was monitoring lawyers and journalists, people raised eyebrows and called you a conspiracy theorist.

Those days are over. Facts allow us to stop speculating and start building, and that’s the foundation we need to fix the internet. We just happened to be the generation stuck with fighting these fires.

Any hope that CITIZENFOUR’s success will help with repatriating its star, or will the Manning treatment forever hang over your head?

[Greenwald] Edward Snowden should not be forced to choose between living in Russia or spending decades in a cage inside a high-security American prison.

DC officials and journalists are being extremely deceitful when they say: ‘if he thinks he did the right thing,he should come back and face trial and argue that.”

Under the Espionage Act, Snowden would be barred even from raising a defense of justification. The courts would not allow it. So he’d be barred from raising the defense they keep saying he should come back and raise.

The goal of the US government is to threaten, bully and intimidate all whistleblowers – which is what explains the mistreatment and oppression of the heroic Chelsea Manning – because they think that climate of fear is crucial to deterring future whistleblowers.

As long as they embrace that tactic, it’s hard to envision them letting Ed return to his country. But we as citizens should be much more interested in the question of why our government threatens and imprisons whistleblowers.

With all the bad news coming out of there, what’s the upside to living in Russia right now?

[Snowden] In the past week, it’s actually been warmer than the East Coast. Wasn’t expecting that one.

Mr. Greenwald, you mentioned before in an article on Canadaland that CBC stonewalled you in a story you were working on with them. Would you be able to elaborate on what happened and what that story was (more or less)?

[Greenwald] I’ve spoken some about this. We had a great relationship with the CBC for months and did some big-impact stories on CSEC:

The reporter with whom we were working left (Greg Weston) – he was great – and then new one who was assigned wasn’t comfortable with the documents, it seemed to us.

But then CBC editors assured us they were committed to doing the reporting aggressively, assigned someone new, and the last story CBC did with us – on mass CSEC spying on file uploads – was, I think, superbly done:

http://www.cbc.ca/news/cse-tracks-millions-of-downloads-daily-snowden-documents-1.2930120

Do you mind people pirating Citizenfour?

[Snowden] I don’t have a commercial interest in the film, so I can’t speak for the filmmakers, but I know what it’s like to be a student with no money.

Ed, is there any truth to the report that Anna Chapman attempted to “seduce” you?

[Snowden] lol no.

I have a filmmaking question for Laura. I’m sure this was probably answered in an interview somewhere, but what kind of legal issues did you run into with this film if any? Was there ever the threat of the footage being seized at customs?

[Poitras] Given the fact that I had been repeatedly detained at the U.S. border because of my work on previous films, I moved to Berlin to edit Citizenfour.

When Ed contacted me in early 2013 I gave him my assurance I would never comply with a subpoena. Before going to Hong Kong I met with many lawyers to assess the risk. I ignored some of the warnings – for instance the Washington Post urged me not to travel to Hong Kong. Another lawyer said not to bring my camera.

In the end I decided I could not live with the decision to not travel to Hong Kong.